"Of the Murderess": A Victorian Tragedy in Leicester

In February 1868 in Leicester, an inquest was held into the deaths of 34-year-old Emma Stone Crofts and her infant daughter, Amy Preston Crofts.

What emerged was a harrowing tale of social ruin, untreated mental illness, and a community (and legal system) that saw the warning signs but could not, or would not, intervene in time.

Seven years prior to her demise, Emma Stone Crofts paused her “immoral life,” and made a home with Charles Crofts, a solicitor’s clerk of respectable standing. The romance, sparked at an open-air gathering, saw the couple move into lodgings near York Place. Their romance did not last. Charles left her, allegedly to take up with another woman, and fled to America. He was never heard from again.

Emma then entered into a relationship with a man named Preston from Grantham. She fell pregnant and was delivered of a daughter, Amy, but by the time Amy was just over a year old, Emma had returned to Leicester, single and visibly in decline. Witnesses routinely saw her intoxicated, disoriented, and voicing suicidal intentions. She often said she would kill both herself and the child.

The first close call occurred when Emma’s sister, Mary Stone, was visiting their parents’ home in Sandiacre Street where Emma was living. Mary was nursing Amy when Emma snatched her from her arms with the words: ‘ Give me my child, and I'll do for it and myself too.” She took a bottle containing a dark liquid from her pocket, and tried to swallow the contents, but Mary and her parents managed to prise it from her, and they pulled Amy out of her grasp too. Emma then took another bottle from her pocket and her family were forced to take that from her too; they ascertained that all of the bottles contained laudanum.

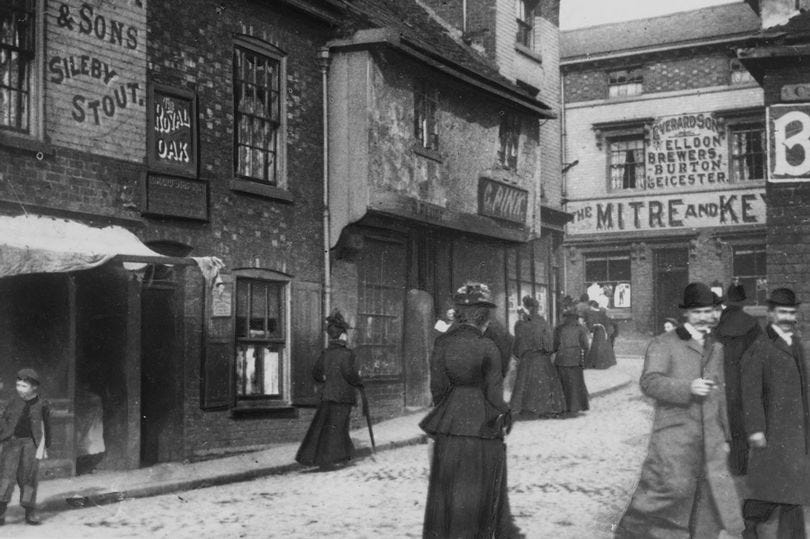

A Victorian Leicester Street.

Three days later, Emma returned home at 1 a.m., behaving erratically. After a day of drinking, she suddenly grabbed her daughter from her mother's arms and fled. A neighbour, Joseph Rudkin, saw her heading towards the canal. Alarmed, he followed. But before he could reach her, she threw off her bonnet and Amy’s hood, then threw the little girl into the water before leaping in herself.

Rudkin rushed to retrieve them, managing to pull Amy out alive but she died shortly after. It took 20-30 minutes to retrieve Emma’s body, which had drifted downstream.

Rudkin testified that only a week prior, he had stopped Emma from doing the same thing. On that occasion, she had whispered chillingly, “If I had got into the water no one would have known anything about it.”

The jury ruled her actions were undertaken whilst“in an unsound state of mind, brought about by her intemperate and profligate habits.”

It later transpired that Croft was set to testify in court as a witness against a man named Thomas Johnson who had been arrested for stealing a glass globe from the door of the Temperance Hotel in Granby Street. However, since she was the principal witness, Johnson was discharged. Had Johnson threatened her not to speak up? Could an appearance in the witness box been yet another weight for Crofts to bear?

We can look back on stories like these and consider Crofts’ motives. Single, forced into a life of sex work to survive, a child in tow, she lived in abject poverty. This coupled with what might these days be perceived as post-natal depression, Crofts could look to nobody for help.

Worcester Journal, 15th Feb 1868

Leicester Journal 14th Feb 1868

Morning Herald 5th Feb 1868

Emma Woodhouse is a historian and author.

She currently has three books published: The Prendergast Watch; Simple Twists of Fate and Mary, Queen of the Forty.

Her next book, Mercy, a true story about a woman from Bridgnorth in Shropshire who was arrested for murder in 1848, comes out in July.

Her first non-fiction book will be published by Pen and Sword Books in 2026.

Emma is also the co-founder of On Creative Writing.